Philip K. Dick and the Science of Friction

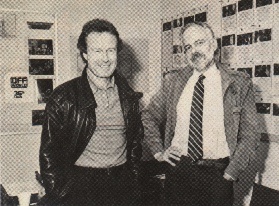

(Above: Philip K. Dick (right) and Director Ridley Scott)

Recently, deciding to find out what all the fuss was about, I picked up a collection of Philip K. Dick's short works (Specifically, The Philip K. Dick Reader) I'd seen the movies, of course. The first of which was Blade Runner some years ago, but I must confess I can't recall a single scene. Needless to say I wasn't interested enough to catch who had written the original novel (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?). Then, this summer, I caught Total Recall and A Scanner Darkly and really enjoyed them both. After that a friend of mine clued me in to Dick's work, and I'm extremely thankful that he did. Philip K. Dick (1928-1982) was an American sci-fi writer who, in my opinion, was what almost every other Sci-Fi writer longs to be: both undeniably readable and thought provoking. Here is a man who writes as though he's seen a ghost, or a whole legion of them for that matter.

Take his "The Hanging Stranger" for a start. The story opens and in a matter of a page we are suddenly plunged into a paranoiac world of alien conspiracy. Here Dick is a pure sci-fi writer, and a brilliant one at that. With a skillfulness that recalls Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s intricate work, Dick makes us feel for ourselves the self-doubt of his protagonists, who are invariably (not to say predictably) desperate to find out whether they are insane or there really are plots forming against them.

In "The Golden Man" and "Tony and the Beetles" Dick tackles the much-treaded subject of world domination, and brings us face to face with the prospect of our obsolescence. In the former, mankind comes into direct contact with homo superior in all his shining glory. In the latter, the insects we so carelessly squash become an intergalactic menace to humanity. But perhaps the most refreshing thing about Dick's work—and indeed, probably the crucial element to his standing out in the veritable sea of lesser sci-fi writers—is the fact that his stories tend to end unresolved. Like a piece of music that ends on a dissonant transitory chord, they leave us hanging. We are left stranded at the edge of some god-forsaken trench on a dark and distant moon in the Betelgeuse galaxy.

This is the friction. The idea of tension is not new, of course, and nowadays Dick's work is so popular that his influence is likely to be found all over the sci-fi universe. However, the questions he brings up in his stories combined with the fact that they just don't end happily forces us to deal with these often-bitter forecasts in a way that most science fiction material simply doesn't. The fact of the matter is, when things don't tie up nicely—when the universe isn’t put back to rights—we are left only with the reality presented us in the story, with no soothing balm of resolution to ease the disturbance that lingers.

Labels: a scanner darkly, blade runner, minority report, Philip K. Dick, science fiction, total recall, writing